Fungal Infections

- related: ID

- tags: #id

The incidence of fungal infection is increasing because of the increased recognition of these infections and an increase in the population at risk worldwide. According to a recent analysis by the Prospective Antifungal Therapy Alliance, the most commonly encountered infections in North America were caused by Candida species (73%) followed by Aspergillus species (14.8%), other yeast (such as Cryptococcus species; 6.2%), and mucormycetes (including Rhizopus species and Mucor species; 1.7%).

Systemic Candidiasis

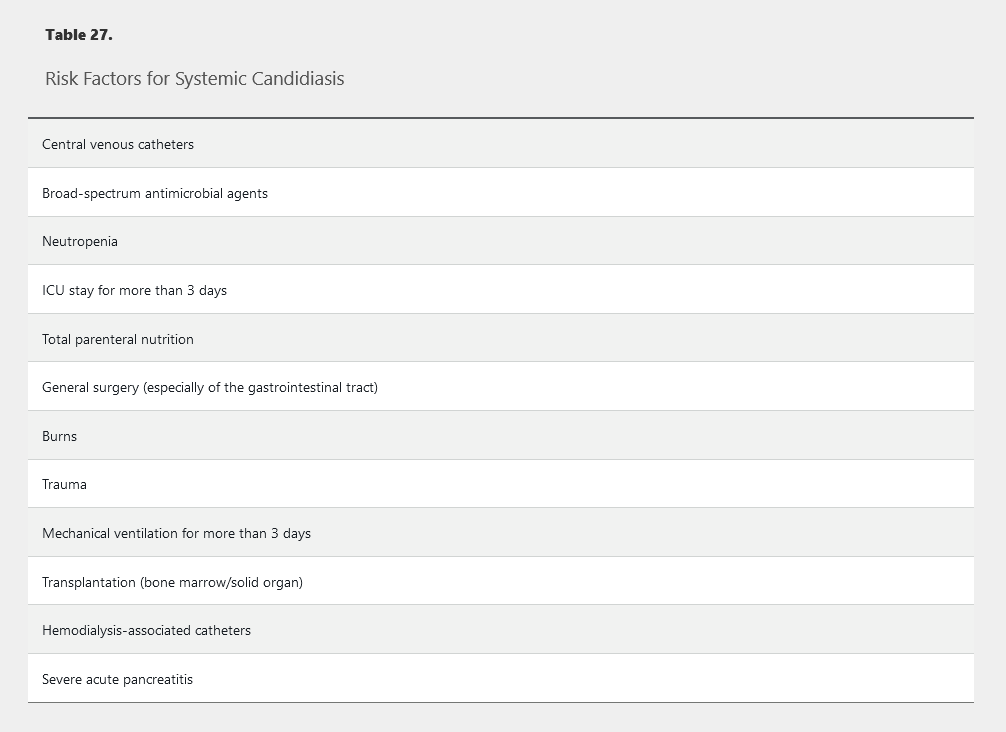

Candida species are the fourth most commonly isolated organisms in bloodstream infections and are associated with a mortality rate of 30% to 40%. Risk factors for systemic candidiasis are listed in Table 27.

Manifestations of candidiasis depend on the organ involved. Candidemia can present as an isolated fever or septic shock. Signs and symptoms of focal infection depend on the site involved (abscess or peritonitis in the peritoneum, empyema in the pleural cavity, or pyelonephritis in the kidneys). Other forms of invasive infection include meningitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and endocarditis. Although often found in the respiratory tract, Candida species rarely cause infections there and are likely the result of colonization. The presence of yeast in the urinary tract (for example, because of the presence of an indwelling catheter) may represent colonization (most commonly) or true infection.

Diagnosis of invasive candidiasis is challenging because only 40% to 60% of patients with infection have positive blood culture results, and cultures can take days to demonstrate growth. Recognizing risk factors (see Table 27) for candidiasis is thus essential to avoid delays in initiating antifungal therapy and resultant increased mortality. The T2 magnetic resonance assay of whole blood provides rapid (within hours) diagnosis of culture-negative invasive candidal infections and can be performed on blood samples even after initiation of antifungal therapy. The β-D-glucan assay also can be used to diagnose invasive candidiasis in patients with negative blood culture results. These assays should be obtained when a patient at high risk (see Table 27) receiving antimicrobial agents is not responding to therapy.

When the Candida genus is identified from a sterile site (blood or tissue), specific species identification is necessary. Although more than 160 species of Candida are known, fewer than 15 produce disease in humans. Additionally, several species (such as C. glabrata and C. krusei) have intrinsic resistance to antifungal agents, especially the azoles, and their proper identification guides therapy.

Treatment of candidemia and invasive candidiasis should include an echinocandin (caspofungin, micafungin, or anidulafungin) and removal of intravascular devices (if possible). However, because of poor penetration of echinocandins into the central nervous system (CNS) and the eye, patients with these infections should be treated with an azole or amphotericin B. Additional treatment of candidal endophthalmitis varies depending on the extent of disease (chorioretinitis with or without macular involvement, vitreous involvement). All patients initially given amphotericin B or an echinocandin may be de-escalated to an oral azole (fluconazole or voriconazole) if the Candida species is susceptible and the gastrointestinal tract is functional. Duration of antifungal therapy for candidemia should be 14 days from the first negative blood culture result in patients with uncomplicated candidemia or 14 to 42 days in patients with invasive candidal infections.

Aspergillosis and Aspergilloma

Aspergillus is ubiquitous in the environment. The most common species are A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. niger, and the amphotericin-resistant A. terreus. Aspergillus produces disease after inhalation of airborne spores (90%) and only occasionally by traumatic skin inoculation. Of all the fungi, Aspergillus is notable for the diverse settings in which it can occur and the various clinical manifestations it can produce.

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, the most serious form of Aspergillus infection, most often occurs in immunosuppressed patients who are neutropenic or are hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients (Table 28). This type of aspergillosis usually begins in the respiratory tract and then enters the circulatory system (angioinvasion). This is followed by the formation of a fungus-septic emboli complex with subsequent hematogenous dissemination. The most common manifestation of angioinvasive disease is pulmonary aspergillosis (60%), but sinusitis, brain abscess, endocarditis, disseminated infection, and osteomyelitis also may occur. Timely diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis is essential to decrease morbidity and mortality, but symptoms and signs are nonspecific (Table 29), and blood culture results are generally negative. In those with suspected invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, serum galactomannan testing is recommended. If the serum galactomannan result is negative, but the patient has strong risk factors, bronchoalveolar lavage with galactomannan and Aspergillus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are recommended, followed by tissue biopsy, if necessary, to establish a definitive diagnosis. Early CT of the chest in patients with suspected invasive pulmonary aspergillosis—with typical findings suggestive of septic emboli (nodules, often with a “halo sign”) (Figure 11), thromboembolic pulmonary infarction (wedge-shaped peripheral densities), or necrosis with cavitation and a crescent sign—and the serum galactomannan assay can be useful in establishing a presumptive diagnosis of invasive infection, especially in neutropenic patients and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, in whom the assay has a sensitivity of approximately 80%. First-line treatment of invasive aspergillosis is with a triazole (voriconazole, posaconazole, or isavuconazole); amphotericin B deoxycholate or liposomal amphotericin B can be used for amphotericin-sensitive Aspergillus species if triazoles are not available. When possible, reversal of immunosuppression improves treatment response.

Other forms of Aspergillus infection occur in different clinical settings. Chronic necrotizing aspergillosis is a semi-invasive indolent form of infection that does not disseminate and occurs in patients who have lesser degrees of immunosuppression (such as those who take chronic glucocorticoids or those who have intrinsic immune defects) or chronic pulmonary disease. Treatment is similar to that for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis results from a hypersensitivity overreaction to Aspergillus species colonizing the respiratory tract; this disorder is seen primarily in patients with cystic fibrosis and occasionally in those with asthma (see MKSAP 18 Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine for more information). Because allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis represents a hypersensitivity response, systemic glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment (sometimes supplemented by antifungal therapy with an azole).

Pulmonary aspergillomas (fungus balls consisting of hyphae, mucus, and cellular debris) may form in patients with pre-existing cavities, such as old tuberculosis cavities and in bullae of patients with COPD; the presence of significant hemoptysis is a potential complication. In the absence of associated symptoms or hemoptysis, pulmonary aspergillomas may not require therapy; however, in the setting of significant bleeding, surgical resection or embolization may be necessary. Antifungal therapy is typically not effective against pulmonary aspergillomas, and its role in aspergilloma treatment is unclear.

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcus is an encapsulated yeast that is ubiquitous in the environment. Although cryptococcal infection can occur in healthy persons, most infected patients have advanced immune suppression, such as AIDS, neutropenia, or organ transplantation. C. neoformans is the most commonly identified species, but C. gattii is seen with increased frequency in the Pacific Northwest region of North America and has been associated with severe and recalcitrant infection. Pathogenesis of cryptococcosis involves inhalation of spores into the respiratory tract, followed by dissemination into susceptible tissues, especially the CNS.

Cryptococcal infection most commonly manifests in the CNS, and cryptococcosis is the most common cause of fungal meningitis worldwide. Clinical manifestations are listed in Table 30, and indicators of a poor prognosis in cryptococcal meningitis are provided in Table 31. Because patients with cryptococcosis-related increased intracranial pressure (ICP) may develop sudden blindness, deafness, or coma, initial opening pressure should be documented during lumbar puncture. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis is essential to diagnose CNS involvement; classic findings include an increased leukocyte count (mainly lymphocytes), an increased protein level, a low to normal glucose level, and the presence of cryptococcal antigen. Serum cryptococcal antigen also is positive in greater than 95% of infected patients; occasionally, blood culture results are positive and thus indicate disseminated disease.

Many symptoms of increased ICP may be improved by cerebrospinal fluid removal through daily lumbar puncture or insertion of a shunt. Aggressive reduction of ICP reduces early morbidity and mortality. Amphotericin B plus flucytosine is the treatment of choice and is effective in more than 90% of patients. HIV-infected patients require maintenance antifungal therapy until they have maintained their CD4 cell counts above 100/µL (100 × 106/L) for a minimum of 3 months and have a suppressed viral load.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasma capsulatum is responsible for one of the most common endemic mycoses in the world. Acquired by inhalation of airborne conidia (bats), this organism primarily produces asymptomatic pulmonary infection. It is distributed along the Mississippi River Valley (Ohio, Missouri, Indiana, Mississippi) in the United States, in Central and South America, in the Caribbean, and in regions of Africa, Australia, and India.

Histoplasmosis most commonly presents with acute respiratory symptoms. Other presentations, in declining order of frequency, include asymptomatic infection, disseminated infection, chronic pulmonary symptoms, rheumatologic symptoms, pericarditis, and sclerosing mediastinitis, oral ulcerations.

The Histoplasma urinary antigen assay has a sensitivity and specificity of greater than 85% in acute and disseminated infection but less than 50% in chronic infection. Identification of the fungus by tissue culture can be a lengthy process but is indicated for clinically suspected cases in which the urinary antigen assay result is negative.

Asymptomatic and mild pulmonary histoplasmosis typically resolves without treatment. Antifungal therapy is recommended for more severe or disseminated disease. Itraconazole is the agent of choice; duration of therapy is 6 to 12 weeks for acute infection and as long as 12 months for chronic cavitary pulmonary infection. For severe lung disease and disseminated infection, liposomal amphotericin B should be used initially, followed by de-escalation to oral itraconazole for an additional 12 weeks.

Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioides is a dimorphic fungus that exists as a mold in the environment. In endemic areas, as many as one third of cases of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are caused by Coccidioides species. There are two species: C. immitis refers to isolates from California, and C. posadasii refers to isolates from all other endemic areas, including Arizona, New Mexico, western Texas, northern Mexico, and parts of Central and South America. In endemic areas, the annual risk of infection is approximately 3% for most persons, although the risk of infection (and dissemination) is greater in those who are pregnant, younger than 5 years or older than 50 years, or of African, Filipino (and possibly other Asian), and Native American ancestry.

Infection is usually acquired by inhalation of aerosolized arthroconidia. Once inhaled, the fungus begins its dimorphic change in the lungs and becomes a yeast cell. Several clinical syndromes are seen in coccidioidomycosis and may manifest as acute or chronic pulmonary infection, as cutaneous infection (~40%), as meningitis (~33%), or as musculoskeletal infection.

Diagnosis is straightforward in endemic areas and usually is based on clinical manifestations and confirmatory testing by a mycologic culture of affected tissue, histopathologic evaluation of tissue, serology for Coccidioides antibodies, or urinary antigen testing.

Fluconazole is the first-line treatment for symptomatic infection. In patients with meningitis, fluconazole is continued for life. In patients who do not respond to azoles, intrathecal amphotericin B may be an alternative.

Blastomycosis

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic, round, budding yeast; daughter cells form a bud with a broad base. Blastomycosis affects immunocompetent hosts. In the United States, blastomycosis is found primarily along the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys but can be found as far north as Wisconsin and Minnesota and as far south as Florida. As with most dimorphic yeast, infection occurs by inhalation of conidia and manifests initially as a primary pulmonary infection (acute or chronic pneumonia). Occasionally, a chest radiograph shows a spiculated nodular appearance that may be mistaken for lung cancer. Rarely, dissemination occurs and produces extrapulmonary disease (osteomyelitis, genitourinary infection, or CNS infection).

Diagnosis of blastomycosis can be made by direct fungal stain of clinical specimens (sputum, tissue, or purulent material) and confirmed by culture or serology for Blastomyces antibodies. Urinary antigen testing is also available. The preferred treatment for mild to moderate infection is itraconazole for 6 to 12 months. Liposomal amphotericin B is recommended for CNS, severe pulmonary, and disseminated infections.

Sporotrichosis

Sporothrix schenckii is a dimorphic fungus found most often in soil, living plants, or plant debris. Although found worldwide, most reported infections are from North and South America and Japan. Infection can occur after direct contact with plants, such as roses and sphagnum moss. Direct inoculation of the organism into the skin or subcutaneous tissue manifests as fixed, “plaque-like” cutaneous sporotrichosis or as lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis presenting as papular lesions along lymphatic channels proximal to the inoculation site. Extracutaneous infection (osteoarticular, pulmonary, ocular, or disseminated) can occur in immunocompromised hosts.

Diagnosis requires culture of the organism from affected tissues. Treatment is with itraconazole and should extend for 2 to 4 weeks after lesions have resolved.

Mucormycosis

Mucormycosis (formerly zygomycosis) is the third most frequent cause of invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts but is rarely seen in immunocompetent hosts. Particularly at risk are patients with neutropenia, diabetes mellitus, and acidosis. The most common mucormycetes are Rhizopus arrhizus and Mucor species. These fungi are commonly found in the environment on decaying organic debris, including fruit, bread, and soil.

Infection is acute and rapidly fatal, even with early diagnosis and treatment. Major blood vessels are invaded, with ensuing ischemia, necrosis, and infarction of adjacent tissues. Mucormycosis has five major clinical forms: (1) rhinocerebral; (2) pulmonary; (3) abdominal, pelvic, gastric, gastrointestinal; (4) primary cutaneous; and (5) disseminated.

Because laboratory studies are nonspecific, diagnosis relies on a high index of suspicion in a host with appropriate risk factors and evidence of tissue invasion, including the characteristic appearance of broad, nonseptate hyphae with acute-angle branches. Serologic tests and blood cultures offer no diagnostic benefit.

Treatment requires reversal of any predisposing condition, extensive surgical removal of affected tissue, and early antifungal therapy. Initial treatment is high-dose liposomal amphotericin B, with later de-escalation to posaconazole or isavuconazole. If amphotericin B is not tolerated, initial therapy with one of the azoles is warranted. Mortality rates remain as high as 60% to 80%, even with therapy.